What is an Omega Creep Test?

Creep is a familiar damage mechanism to most of us within the industry. Creep occurs when exposure to elevated temperatures results in the permanent deformation of a material at a stress below its yield strength at that temperature. At most facilities, creep is commonly associated with fired heaters and boilers, and sometimes with piping and equipment. API 579 presents fitness-for-service (FFS) procedures for addressing creep damage and remaining life. However, another less well-known strategy for handling creep damage and remaining life is Omega creep testing. This Industry Insights article will define an Omega creep test, explain how it differs from other creep damage analysis techniques/testing, and present the benefits of performing an Omega creep damage analysis to accurately diagnose current damage and further extend fired heater tube remaining life.

The most common misconception regarding Omega testing is that the actual laboratory setup differs significantly from a traditional creep test. This is not actually the case; hence, the term “Omega testing” may be confusing. The key differences between an Omega test and a traditional creep test are in the analysis and the exposure flexibility, not the laboratory setup. Thus, an Omega analysis still utilizes a traditional creep laboratory setup, measuring the amount of material deformation under a specified load (stress) at a specified temperature. The Omega analysis is easily able to accommodate multiple temperatures and stresses on a single specimen, compared to a conventional creep rupture test. Omega assessments are also not required to be run to rupture, as the parameters of interest (Omega and initial strain rate) can be obtained much more quickly than specimen rupture at a given stress and temperature. This flexibility – the ability to change conditions mid-test and extract more information from the same specimen – is an advantage of an “Omega test”(i.e., a creep test utilizing Omega analysis). An Omega analysis can be performed on any creep strain vs. time data, even conventional creep tests performed at a single temperature and stress.

A standard creep testing apparatus includes the test sample, typically a dog-bone specimen similar in configuration to a tensile test specimen (can be base metal or a cross-weld specimen); the applied load, usually weights suspended from the test specimen; and an extensometer to measure the specimen gage length throughout the test. The specimen housing is contained within a furnace to allow for elevated temperature tests, with a thermocouple(s) attached to the specimen for accurate temperature control. Creep elongation (or strain) is defined as the change in length (inch/inch, or commonly a %) as measured by the extensometer. Test data is commonly presented as a graph of creep deformation or strain (%) vs. time. This allows for quick observation of the specimen strain throughout the test duration, as well as easy determination of a creep rate (inch/inch/hour) equivalent to the slope at any point in the test.

What is an Omega Analysis?

Now that we have established the laboratory testing methodology is consistent with a traditional creep test, what makes an Omega creep analysis unique, and how is it performed?

The Omega analysis methodology was developed by the Materials Property Council (MPC) and is commonly referred to as the MPC Omega method. The classical creep curve consists of initial primary creep, followed by secondary creep, and finally tertiary creep until specimen ruptures. The Omega method largely neglects primary creep due to it not being significant in service and because it is generally accounted for when testing. The Omega method creep curve also considers primary and tertiary creep to both initiate at the start of testing, time 0. This results in an overall curve that maintains the classic creep curve identity when the primary and tertiary curves are combined. The tertiary portion of the creep curve and eventual rupture time are defined by the initial strain rate (έ₀) and Omega (Ω) parameters. Physically, the Omega parameter is the acceleration of strain rate as strain accumulates in the specimen. Historically, one of the most common creep analysis models is the Larson-Miller relationship. The Larson-Miller parameter is a function of stress with a variable material-specific constant, CLM. While material-specific optimized Larson-Miller constants have been developed, originally a CLM value of 20 was used for ferritics, and a CLM value of 15 was used for austenitics. The Omega method and Larson-Miller models are mathematically related, and for many materials the coefficients for Omega and strain rate calculations can even be calculated from Larson-Miller rupture times. This raises the question: “Why should the Omega method be used when Larson-Miller is simpler and already more widely used?” One reason, and likely the most justifiable, is that the Omega method can incorporate creep testing results into remaining life calculations faster and much more easily than the Larson-Miller relationship. This allows for increased value in creep testing ex-service material, with more accurate remaining life calculations and shorter analysis turnarounds. It is important, however, to ensure the creep test produces sufficient data to determine an Omega parameter and that the data is manipulated properly. Otherwise, due to numerical constraints, unrealistic material properties may be produced. Out of rupture time, initial strain rate, and Omega values, Omega has by far the least amount of available data, even considering the MPC Omega database. Due to this lack of data, equation constraints and fitting techniques may produce Omega values that stray from physical expectations. To avoid this issue, it is important to either produce sufficient tertiary creep data during the creep test to allow for an Omega value to be fit or compare the test results to other tertiary creep test data for the same material.

Executing an Effective Creep Test

While the creep test laboratory setup to perform an Omega analysis is similar to a standard creep test, there are important test considerations that influence the effectiveness of the analysis and can affect the final results.

Some important variables to consider include the following:

- Specimen location – which tube(s) in the firebox as well as what side/end of the specific tube.

- Specimen orientation – whether a longitudinal or circumferential specimen or both should be used.

- Test conditions – applied stress and temperature, and based on those selections, the range of anticipated test durations until rupture. From a financial and logistical perspective, it is important to select test conditions that result in exposure durations that are manageable and provide results in an effective timeframe. Waiting years for a creep test to run to completion is not efficient from a cost or results implementation standpoint. On the other hand, the aggressiveness of test conditions must be considered and cannot stray too far from actual service conditions.

- Testing one specimen at multiple temperatures or stresses – as long as sufficient tertiary creep data is obtained at one condition to calculate a realistic Omega value, the temperature or stress of the test can then be altered to obtain an additional Omega value and/or to shorten or lengthen the time to rupture. Test conditions cannot be altered during a traditional creep test.

- Oxidation of the test specimen – whether this needs to be accounted for during exposure. This is dependent on the material-specific oxidation rate at the test temperature. Application of a Ni or Cr coating may be recommended for longer-duration tests of carbon and low-alloy steels.

Answering these questions and selecting test variables are extremely important considerations that can make or break the final test results in terms of applicability and confidence. This is why it is critical to have an experienced materials & corrosion engineer review all tube extraction and specimen preparation plans as well as creep test setup and operation. For example, a creep test specimen extracted from the cold side of a heater tube may have vastly different creep properties than a specimen extracted from the hot side of the tube, in addition to other possible microstructural degradation, such as carburization. A circumferential specimen may identify substantially more accumulated creep damage as compared to a longitudinal specimen from the same tube due to exposure to hoop stresses that are typically higher than the axial load stress during operation. For this reason, nearly all Omega testing projects on heater coils of significant operating pressure include at least one circumferential specimen. Selection of test conditions that stray significantly from in-service conditions may produce results that cannot confidently be applied to the ex-service material in question, leaving little confidence in analysis results.

To ensure Omega testing can be used with high confidence in making replacement decisions, it is most effective to review each tube remaining life analysis on a case-by-case basis for optimal accuracy of test procedure, results, and analysis. E2G has made these decisions for countless creep test procedures and remaining life analyses.

Utilizing Test Results & Performing an API 579 Remaining Life Analysis

Effectively analyzing creep test data can have a significant economic impact due to the number of conservative assumptions that must be made if test data is unavailable. In the absence of test data, lower bound material properties are typically assumed, which can be significantly more limiting than actual material properties, resulting in up to 1/10th the rupture life at the same test conditions! This correlates with more tube replacements that may not be necessary, and possibly extended downtime. Performing a creep test on ex-service material allows for specific tube properties to be known, generating custom Omega and strain rate properties. These properties likely vary from average material properties, such as those published in Part 10 of API 579/ASME FFS-1 (API 579) Fitness-for-Service, and are instead representative of the specific tube tested. The strain rate and creep ductility adjustment factors (ΔΩCD and ΔΩSR) within the Omega method equations allow up to a 40x difference between lower bound and upper bound material properties for a given alloy. These adjustment factors can be obtained from comparing ex-service material creep test results to expected average virgin material properties. The cost to perform a creep test and remaining life assessment is also a fraction of the cost of a heater re-tube.

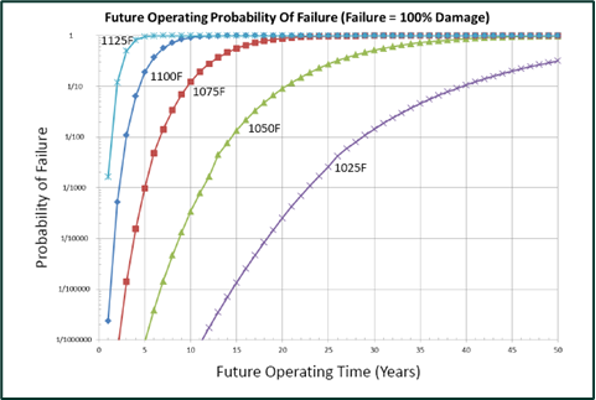

Once the tube-specific custom material properties are established, a formal remaining life assessment can be completed based on the equations and analysis methods outlined in API 579. In most assessments, E2G models remaining life calculations up to 100% tube damage; however, a safety factor can be applied if desired. In general, a margin is applied for added conservatism to the service conditions used in the FFS assessment, rather than just a factor applied to the final remaining life value.

A major advantage of physical creep testing compared to calculations alone is that remaining creep life can be determined in the absence of past operating data. The creep damage from installation to the present is “baked in” to the Omega and strain rate properties measured during the test, and the FFS assessment for creep remaining life only needs to consider future operation. However, it should also be noted that a key input in remaining life calculations is as much of the past operational history of the tube as possible. This allows the FFS analyst to use temperature and pressure basis for future operation that accurately replicates past (or at least, recent past) operation. Remaining life assessments can also be performed on virgin material to determine variance from literature properties; however, this is uncommon and generally provides less value than performing an assessment on ex-service material.

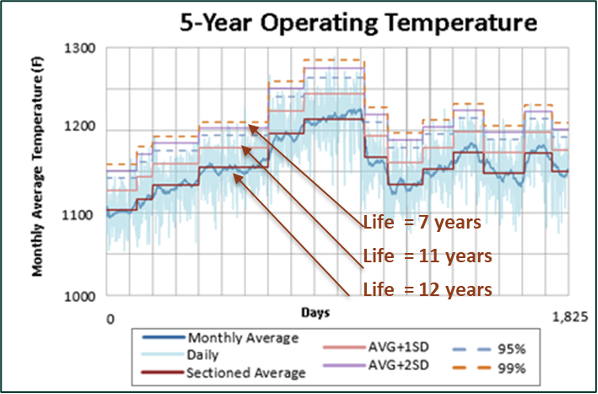

The more past operational data (temperature and pressure) that is available, the higher confidence in the assessment. Depending on the specific heater application, operating conditions may be subject to change based on fuel gas firing, coke deposition, catalyst effectiveness, etc. varying throughout the run duration. Daily tube metal temperature (TMT) data is essential in painting a picture of the tube exposure history and identifies any possible operational upsets that may have occurred. When presented with such data for modeling current tube damage, E2G will analyze the past data, smoothing out noise and erroneous data points, to create an accurate temperature profile with minimal added conservatism. Providing operating data also allows for parametric studies to be performed, examining changes in future operating conditions and how they affect the expected remaining life. For example, the remaining life can be modeled at future operating conditions that mimic past operation, as well as future conditions that are more severe (higher temperature and/or pressure) or less severe (lower temperature and/or pressure). This is key if an owner-user expects different future operation or operational changes throughout the run length. These studies may also allow for cost-benefit economic analyses to compare the increased product yield at elevated operating conditions vs. the reduced heater tube remaining life due to more severe operation.

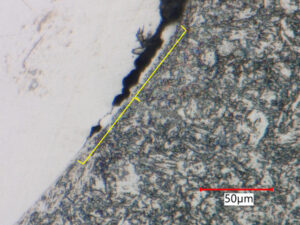

E2G typically recommends a reassessment interval that corresponds to half the predicted remaining life to ensure damage accumulation is following predicted levels. This reassessment could include extraction of another sample and creep test, field metallography, a revised FFS assessment with new operating data, etc. If future operation conditions are expected to vary from the modeled conditions, or if simply desired, this interval can be altered to one-third or one-quarter of predicted remaining life for an additional safety measure. Additional analysis techniques such as probabilistic life assessment; metallographic profiling to identify carburization, creep voids, or other microstructural degradation; tensile tests; detailed dimension measurement (O.D. growth); and hardness/microhardness testing can aid in understanding the level of creep damage in the material. With numerous variables that make every remaining life assessment unique, it is imperative that an experienced metallurgist oversee all steps in the assessment process. If the correct test conditions are selected and appropriate analysis techniques deployed, an Omega creep damage assessment can provide significant value to an owner-user that is hesitant to undergo a large re-tube or wants to minimize unnecessary downtime. Slight variances in model inputs or interpretation of results can greatly reduce value obtained from remaining life assessments that may have taken months to procure. Just like heater tube remaining life, Omega method assessments should not be left to chance.

Key takeaways:

- E2G has performed Omega creep testing projects on hundreds of fired heater tubes.

- We have helped owner-operators extend heater coil life and justify delaying retubes (i.e., avoid leaving “meat on the bone”).

- We have one of the most extensive databases of high-temperature material data that can be used to explain creep specimen behavior and develop properties for materials not included in API 579.

- Our engineers perform detailed analysis of operating data to use in conjunction with measured creep properties to provide the most accurate remaining creep life assessment possible.

- Our state-of-the-art FFS software allows us to run many different future operating scenarios as part of the assessment.

If you have a creep-related challenge and think that Omega testing or detailed creep analysis might help, please fill in the form below to contact the author: