Introduction

Dents are common anomalies in fixed equipment and pipelines. This unique form of damage is caused by a variety of sources. Typical causes of dents in buried pipelines include impact from an excavator and laying the pipeline on rocky soil. For fixed equipment or aboveground piping, dents may be formed by accidental impact or overload during construction and installation, or while moving materials around equipment during maintenance activities. In all cases, a dent is characterized by a permanent, inward deformation of material caused by mechanical forces. There may be metal loss associated with the dent in the form of gouging, where material is removed, and the impacted surface is work-hardened by the indenter. Additionally, the act of forming the dent may induce cracking or make the dented region more susceptible to cracking in the future, particularly under cyclic loading conditions.

The most common dents found in pressurized equipment and piping are plain, smooth, single-peak dents in cylinders without gouging, where the dent can be characterized with a depth and radii of curvature in both principal directions. For such scenarios, several assessment procedures exist to evaluate the component’s susceptibility to failure and continued fitness-for-service (FFS). To evaluate whether a dent poses a viable threat to the integrity of a component, the dent’s potential failure mechanisms must be understood and susceptibility assessed. For components that operate under internal pressure, the following failure mechanisms must be assessed:

- Plastic collapse – Does the presence of the dent reduce the pressure-carrying capacity (i.e., burst pressure) of the component?

- Local strain – Does the plastic strain associated with the formation of the dent (combined with the plastic strain from the initial formation of the component) exceed material limits such that the dent may initiate surface cracking?

- Fatigue – Will the dented component undergo cyclic loading in the future? If so, will the stress riser caused by the dent reduce the component’s fatigue life?

This article will cover several common analysis methods for one or more of these critical failure mechanisms, plus discuss other, less common potential failure mechanisms such as creep and more complex dent configurations.

Plastic Collapse

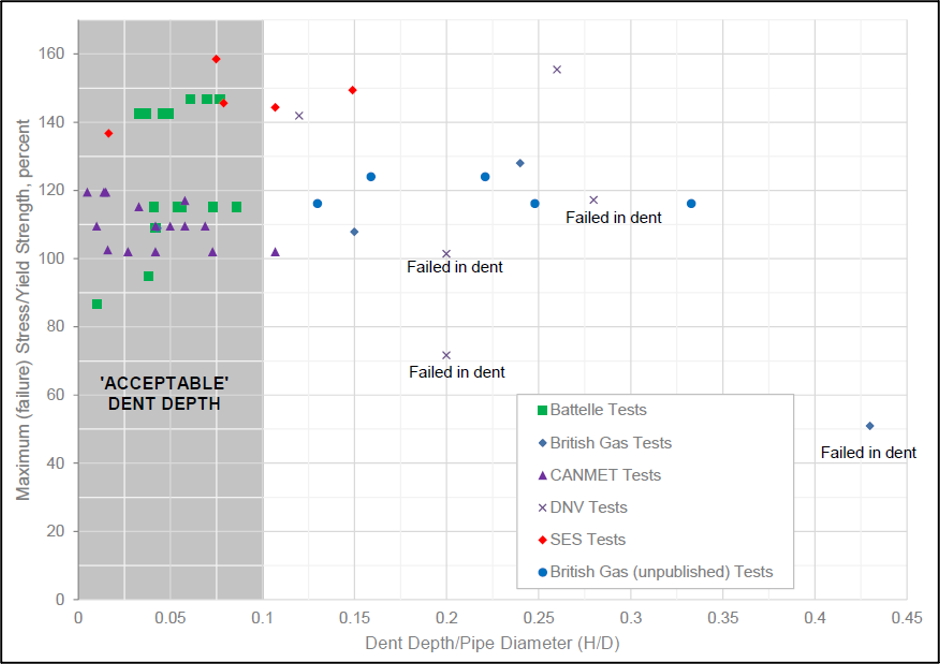

In general, relatively shallow dents are not expected to reduce the pressure-carrying capacity (burst pressure) of a cylinder. When internal pressure is applied to a dented cylinder, the dent will tend to “re-round” back toward its original circular cross section. Physical testing has shown that plain dents with unpressurized depths less than 10% of the outside diameter of the cylinder do not decrease the pressure capacity of the cylinder (i.e., no reduction in burst pressure); see Figure 2 below [1].

Figure 2 indicates that most of the tested pipeline steel samples failed near or above the specified minimum yield strength of the material, and none of the samples with dent depth-to-pipe diameter ratios less than 20% failed in the region of the dent itself.

The 10% limit for unpressurized dent depth is repeated in the Level 1 procedure in Part 12 of API 579-1/ASME FFS-1 (API 579) [2], modified to 7% depth when pressurized; this assumes that application of internal pressure reduces the dent depth. The API 579 procedure is based on the Pipeline Defect Assessment Manual (PDAM) and is applicable to common pipeline sizes (NPS 6 to NPS 42) and thicknesses (0.200 inches to 0.750 inches / 5.08 mm to 19.05 mm) since the physical testing was performed on pipeline samples. This presents a challenge when assessing dents in pressure vessels, which commonly exceed the size limits of applicability. In these cases, detailed Level 3 analysis is required to evaluate the dent for plastic collapse. However, limited Level 3 finite element analysis (FEA) studies of shallow plain dents in large cylinders do not indicate greater concern for plastic collapse than that suggested by PDAM.

Local Strain

From a static loading perspective, local strain failure is the most concerning failure mode for plain dents. The strain of formation of the dent may locally exhaust the ductility of the material and initiate a crack. This strain is not dependent on the depth of the dent but rather on the local curvature within the dent. As such, determining the cross-sectional profiles of the dent in both circumferential and longitudinal directions is extremely important in assessing the dent forming strain.

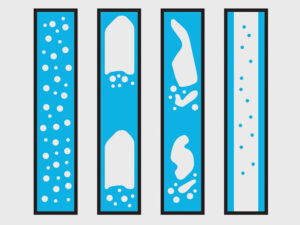

For pipelines, in-line inspection (ILI) is commonly performed with caliper pigs (Figure 4) that can obtain measurements of deviation from a circular cross section.

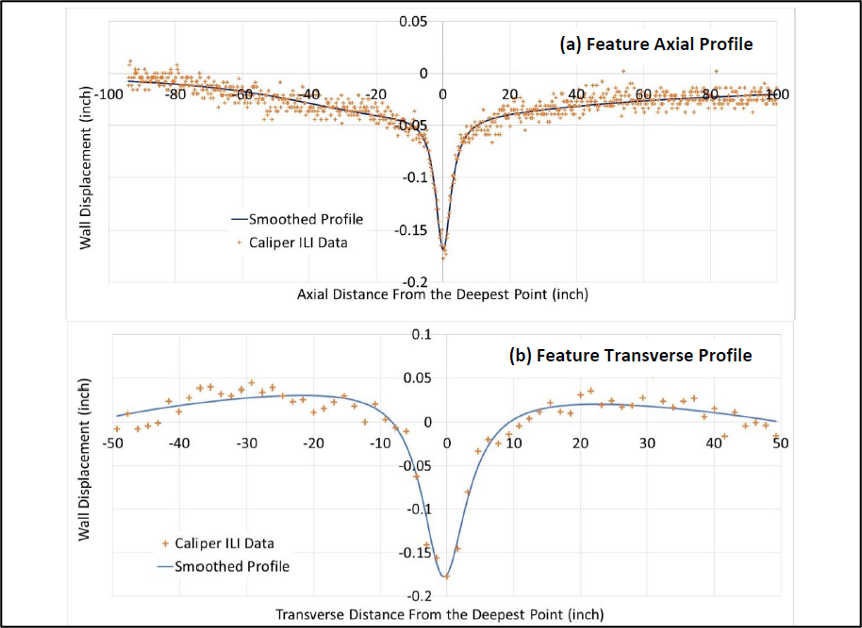

The challenge with ILI data is filtering and smoothing the data to obtain a usable dent profile and radii of curvature at the base of the dent for an accurate engineering assessment. Figure 5 is an example of caliper pig data for a dent with smoothed profiles from API RP 1183 [3].

For fixed equipment and aboveground piping, access to the dent is typically not an issue, so physical measurements can be taken to obtain cross-sectional profiles. These may be obtained with grid data using pit gages or depth micrometers, or by laser scanning. Curves will still need to be fit to the data and may require filtering or smoothing (especially considering surface finish may not be completely uniform) to determine usable radii of curvature in an assessment.

For piping or smaller equipment that falls within the limits of applicability of PDAM and API 579 Part 12, Level 1 (the same assessment methodology is used in both documents), the dent radius of curvature (in the base of the dent) simply needs to exceed five (5) times the cylinder thickness to meet the forming strain requirement. This is based on physical testing results presented in PDAM and, therefore, is not applicable to sizes outside the limits of testing and does not provide a quantitative assessment of strain. For cases outside these limits, a detailed Level 3 assessment is required.

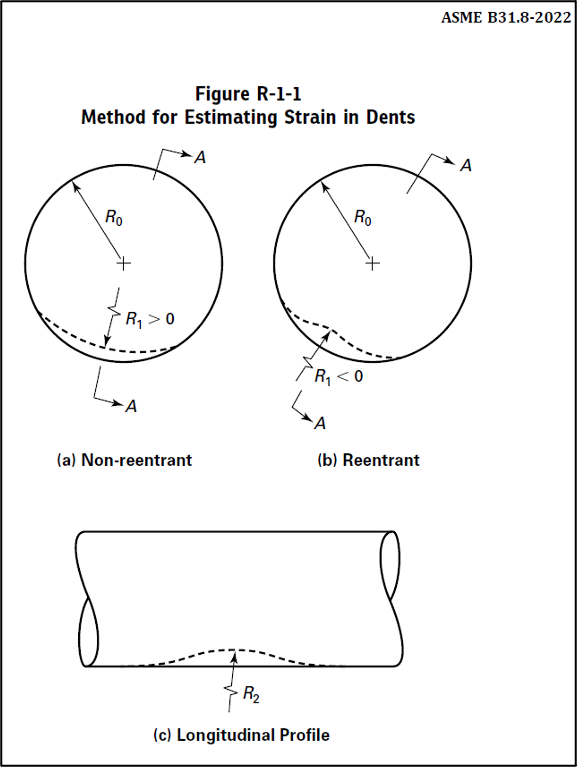

API RP 1183 paragraph 7.2 provides closed-form dent strain calculations taken from ASME B31.8 [4] Appendix R. The 2021 edition of API 579 includes reference to the methodology in API RP 1183 as an option in a Part 12, Level 3 dent assessment. These calculations use the radii of curvature (see Figure 6) at the base of the dent in both circumferential and longitudinal directions, along with equations derived from thin shell and beam theory, to determine principal direction strains at the inside and outside surfaces. The principal strains are used to calculate equivalent strains at each surface, which are then compared with limits established in API RP 1183:

- 40% of average elongation from material test reports (MTRs)

- 50% of specified minimum elongation

- 6% strain with no material information

- 4% strain if the dent is coincident with a weld

For plain dents remote from structural discontinuities with no gouging and no abnormal features, the ASME B31.8 Appendix R closed-form strain calculations provide a good approximation of the forming strain at the peak of the dent.

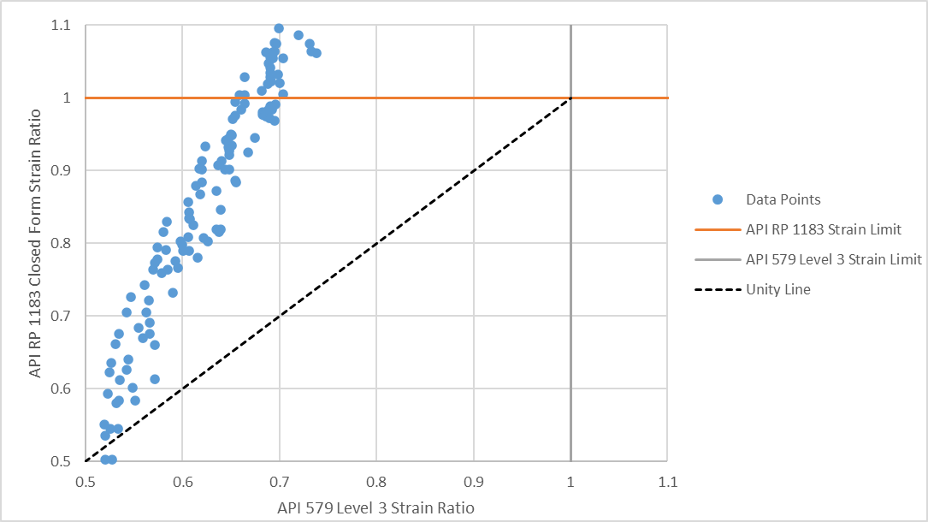

A detailed API 579 Part 12, Level 3 assessment utilizes elastic-plastic FEA and evaluates local failure protection using a triaxial plastic strain ratio. This plastic strain ratio is material-dependent and is a function of the calculated principal stresses. E2G performed limited parametric studies to compare the strain ratio set in API RP 1183 with the API 579 Level 3 triaxial strain ratio. Comparison of the API RP 1183 strain ratio versus the API 579 Level 3 strain ratio for the dented cylinder geometries and SA-516-70 carbon steel material chosen in the study is presented in Figure 7. These results indicate the API RP 1183 strain ratio is conservative compared with the API 579 Level 3 strain ratio. While there may be value in performing a detailed Level 3 assessment, the conservative results achieved with the simple closed-form calculations provide a vastly simplified analysis procedure. This study should be expanded to confirm the behavior is consistent outside the bounds of the analyzed cases.

Fatigue

For dented components in cyclic service, a fatigue evaluation considering the complete operating history and the stress concentration at the dent must be performed. This is typically only a concern with liquid pipelines where many pressure load variations occur over the life of the pipeline. Most gas pipelines, process piping, and pressure vessels do not operate cyclically beyond the simplified fatigue screening limit of 150 cycles over the life of the equipment from API 579 Part 14.

If fatigue is a concern, an API 579 Part 12, Level 2 assessment, based on the PDAM methodology, can be used to determine fatigue life using the same dent radius of curvature that is employed in the Level 1 procedure. This method effectively performs an S-N fatigue calculation with a stress concentration factor based on dent radius and is correlated to fatigue test data for dented pipelines, as documented in PDAM. Given this basis on testing, the applicability and limitations from the Level 1 procedure apply, meaning that typical pressure vessels will fall outside the size limits. In these cases, a detailed Level 3 analysis is required to determine fatigue life.

API RP 1183 provides several fatigue life screening and assessment methods for liquid pipelines. The applicability of each method depends on the depth and restraint condition of the dent. Each method requires some knowledge of at least one year of operational pressure data (past and/or future) at the location of the dent. If data is only gathered at pump stations, an interpolation procedure that accounts for the pressure gradient along the pipeline must be used to determine the pressure history at the location of the dent. The Level 1 fatigue life screening methods are suitable for ranking the severity of dents, while the Level 2 assessment methods provide an estimate of remaining life and require detailed ILI geometric data of the dent. Similar to API 579, API RP 1183 determines fatigue life using a conservative S-N curve that is based on experiments of full-scale specimens.

Other Considerations

This article is primarily focused on plain, smooth, single-peak dents in cylinders remote from geometric and material discontinuities. While this covers the majority of dents, other cases can cause a higher failure concern and typically require detailed non-destructive examination, Level 3 analysis, and/or repair.

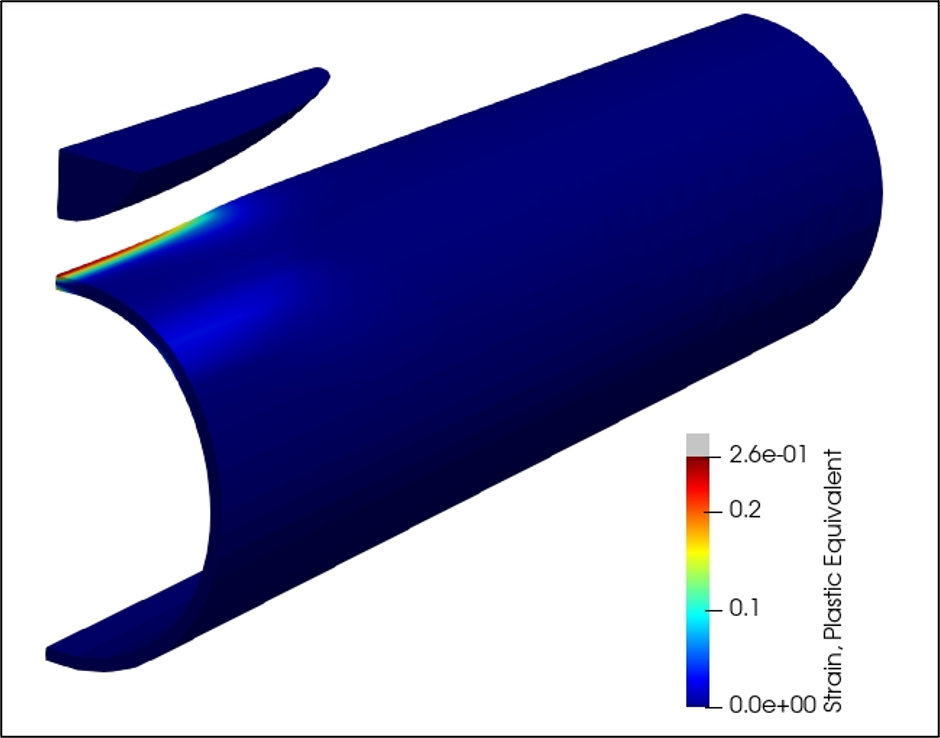

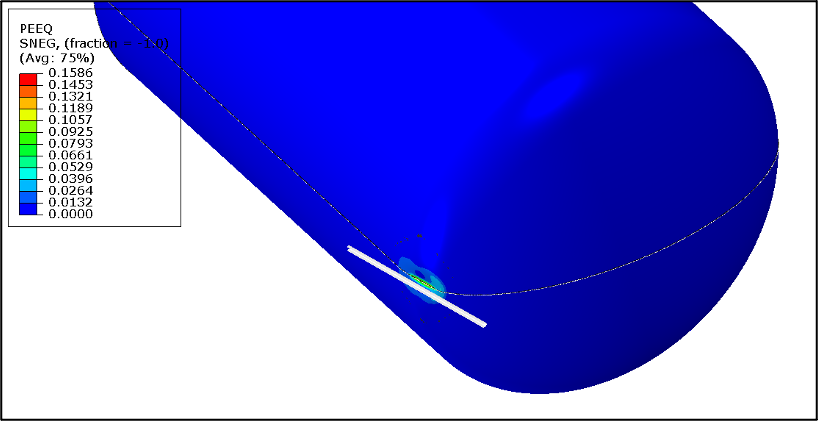

- Dents near structural discontinuities: The common dent assessment procedures are only applicable to dents in cylinders remote from discontinuities. Elevated stresses and plasticity at local discontinuities are exacerbated by dents and require Level 3 analysis. Figure 8 shows an example FEA of a dent in the knuckle of a formed head on a pressure vessel.

- Dents subject to external pressure or other compressive stress: Components in compression may be highly sensitive to imperfections or deviations from true cylindrical form. Part 8 of API 579 provides procedures consistent with design codes to address small deviations, but dented components subject to compressive loading will in most cases require Level 3 buckling analysis, repair, or replacement.

- Kinked dents or constrained dents (where the indenter remains in place, such as a rock dent in a buried pipeline) with a sharp indenter profile: Sharp discontinuities significantly increase the stresses and strains on the pipe surface and can be extremely limiting with respect to local strain and fatigue. As such, cracking (either present or future) is a significant concern and will typically require repair. Inspection for cracking on the inside surface of a pipe with a kinked dent is extremely challenging.

- Multi-peak dents: These geometries cannot be simplified in the same manner as single-peak dents and as such require detailed Level 3 analysis.

- Dents at welds: Longitudinal or circumferential welds introduce uncertainty with respect to quality (i.e., presence of weld defects) and potential toughness concerns such that failure due to cracking and rupture needs to be assessed. PDAM, Edition 2.1, (August 2024) includes a reduction in dent depth limits from 4% of the pipe outside diameter (Edition 2, 2016) to 2% based on rupture tests performed on dents interacting with welds. The Level 1 procedure in Part 12 of API 579 uses a depth limit of 4% per PDAM 2 and is currently non-conservative compared to PDAM 2.1.

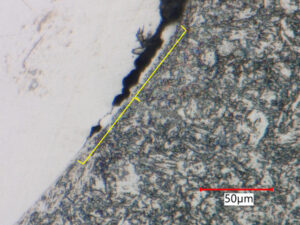

- Gouging: Dents with gouges are a severe damage condition due to the material removed and the work-hardened surface layer that results from formation of the gouge. These anomalies are more susceptible to cracking and are often recommended to be repaired or replaced. If the work-hardened layer can be removed by surface grinding and any sharp geometry from the gouge is blended smooth, API 579 allows the damage to be evaluated as just a dent while also considering the reduction in strength from the metal loss.

- Dented components with significant supplemental loads: The common dent methods are intended to assess cylinders under internal pressure only. If supplemental loading due to weight, wind, seismic, etc. is large, this may govern the failure of a dent and require Level 3 analysis. In some circumstances, additional supports may be installed to alleviate concerns for supplemental loading.

- Dented components in the creep range: The common dent rules do not address components operating in the high-temperature creep range for any materials. Creep damage can accumulate rapidly at local discontinuities such as dents and significantly reduce the remaining life of a component. Level 3 analysis is required to assess dents in the creep temperature range.

Conclusions

For plain, smooth, single-peak dents in cylinders that operate under internal pressure, there are several simplified engineering methods to determine if the dents are fit for continued service. It is critical to understand the applicable failure modes for the equipment being assessed, as the assessment may be simplified if it is not in cyclic service.

Relatively shallow dents are expected to be limited by concern for crack initiation due to dent forming strain rather than plastic collapse related to dent depth. For dented components in cyclic service, such as those in liquid pipelines, simplified fatigue analysis methods are available. Pressure vessels that fall outside the geometric limits of common pipeline sizes (larger than 42 inches / 1066.8 mm in diameter or greater than 0.75 inches / 19.05 mm thick) require more detailed analysis. However, future work may be completed to relax the current geometric limitations associated with the typical dent assessment procedures.

Please submit the form below with any questions for the authors:

References

- The Pipeline Defect Assessment Manual Edition 2.1, Penspen, August 2024.

- API 579-1/ASME FFS-1, Fitness-For-Service, December 2021.

- API Recommended Practice 1183, Assessment and Management of Pipeline Dents, November 2020 with January 2021 Errata and May 2024 Addendum.

- ASME B31.8-2022, Gas Transmission and Distribution Piping Systems.