Why Piping Systems Matter

Piping systems are everywhere—from chemical plants and oil refineries to power stations and municipal water services. For many early-career engineers, pipes are among the first things they notice when stepping onto a site or reviewing facility diagrams, yet the complexity behind their design and performance isn’t always obvious at first glance.

Understanding certain aspects of piping systems is foundational for anyone involved in mechanical, process, or facilities engineering. Reliable piping enables the safe transport of fluids—gases, liquids, slurries—between pieces of equipment and across entire plants. Failures in these systems don’t just lead to operational outages; they can also result in major safety hazards, environmental releases, and substantial financial loss. In other words, piping systems are vital to almost every engineered process.

Where You’ll Encounter Piping Systems

Typically, engineers interact with piping systems in several scenarios:

- Design projects: Creating new or modified process lines

- Site visits: Inspecting physical piping, investigating leaks or corrosion

- Maintenance: Supporting repairs, upgrades, or integrity assessments

- Interdisciplinary coordination: Working alongside process, civil, and mechanical teams where co

–operation is required

Regardless of your role, a solid grasp of piping fundamentals prepares you to spot issues, communicate effectively, and contribute to safe, cost-effective engineering solutions.

Core Concepts: Key Terms & Principles

What is a Piping System?

Simply put, a piping system is an interconnected network of pipes, fittings, valves, supports, and sometimes specialty items (e.g., expansion joints and flexible hoses). Its main function is to contain and direct the flow of process fluids between designated points—such as from a reactor to a heat exchanger, or from a pump to a storage tank.

Major elements of a piping system include:

- Pipe: Tubular product (often steel, plastic, or copper) that serves as a fluid pathway

- Fittings: Pieces that connect pipes together—elbows, tees, reducers

- Valves: Control devices for regulating flow or isolating sections

- Flanges: Enabling connection/disconnection at specific junctions

- Supports/hangers: Maintaining pipe alignment, preventing sagging, reducing vibration

To return to the basics of these complex systems, an effective piping system must:

- Contain the fluid (without leaks)

- Withstand design pressures and temperatures

- Accommodate flow rates efficiently and safely with an acceptable amount of pressure drop

- Handle expansion, contraction, and movement (from thermal effects, pressure surges, seismic events, or equipment vibration)

- Avoid interference issues to enable maintenance and future access

Engineers select materials, sizes, and layouts not just to meet process requirements, but also to withstand expected stresses over years of service. Integrity refers to a piping system’s ability to perform its intended function safely, reliably, and in compliance with regulations over its service life. Integrity management includes:

- Preventive design (correct materials, correct wall thickness, proper joints)

- Inspection and monitoring (spotting damage, corrosion, or aging)

- Repairs and rehabilitation (restoring function when issues arise)

Why Engineers Should Care: Safety, Reliability, and Compliance

Safety: Failures such as ruptures, leaks, or uncontrolled releases can have catastrophic consequences—including fires, explosions, toxic exposures, and environmental harm. Good design and maintenance practices reduce the risk of these events.

Reliability: Downtime due to piping failures stalls production, disrupts schedules, and leads to costly unplanned work. Reliable piping design considers not just the worst-case scenario, but also wear-and-tear mechanisms over time.

Compliance: Various codes—such as ASME B31.3 for process piping—outline minimum requirements for design, construction, and inspection. Regulatory compliance is non-negotiable, but good engineering often goes beyond the bare minimum for added assurance.

Common Problems and Failures in Piping Systems

Mechanical Failures

- Leaks: Most often at joints (flanges, threaded connections) or due to corrosion/perforation in pipe walls

- Fatigue cracks: Caused by cyclic loading, vibration, or thermal expansion/contraction

- Overpressure bursts: Resulting from blocked lines, failing pressure relief, or control system malfunctions

Corrosion and Material Degradation

- Internal corrosion: Caused by process fluids (acids, water, oxygen)

- External corrosion: From atmospheric exposure (humidity, salt spray, industrial pollutants)

- Stress corrosion cracking: Combined effect of tensile stress and corrosive environment

Structural Issues

- Pipe support failure: Leading to sagging, misalignment, or overstress

- Thermal expansion: Unaddressed, causes bowing, joint failure, or unwanted force transfer to connected equipment

Operational Hazards

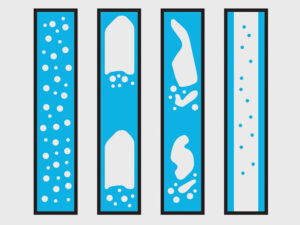

- Water hammer: Sudden changes in fluid velocity (e.g., valve closure) causing pressure surges

- Incorrect materials: Using pipe or fittings not compatible with fluid, pressure, or temperature

Case Study: Resolving Vibration-Induced Fatigue in a Process Piping System

To illustrate how these common problems and failures can play out in practice, let’s look at an industry example in which a mid-size chemical plant noticed small leaks recurring at the welded junction between a process pipe and a heat exchanger. While immediately manageable, the pattern suggested a systemic issue that could threaten integrity over time.

Site observations: Inspection revealed that minor cracks were developing at the weld. With rotating equipment (pumps, compressors) nearby, the engineering team suspected vibration-induced fatigue as the root cause.

Approach: The team performed field vibration monitoring and discovered the pipe was experiencing vibration amplitudes above recommended safe limits.

Solution: Additional pipe supports were installed closer to the heat exchanger nozzle, which reduced the vibration levels at the span of piping that experienced the failures. Weld details were improved and other similar sites were inspected.

Result: Post-modification monitoring confirmed vibration levels had dropped to within safe limits. Follow-up inspections showed weld cracks did not recur, and downtime from leaks in the unit went down sharply.

Takeaways:

- Vibration can cause hidden but serious fatigue failures in piping.

- Early warning signs (small leaks, visible cracks) should prompt investigation beyond surface repairs.

- Collaborative analysis and straightforward mechanical fixes—like support placement and routing changes—enhance integrity and reliability.

Common Misunderstandings and Pitfalls

Underestimating forces: Pipes experience not just internal pressure, but external forces such as thermal movement, vibration, wind, or accidental bumps. Missing thermal expansion loops or proper support can result in hidden damage and failure.

Neglecting Connections: Joints—especially flanges and welds—are common leak locations. Pay close attention to installation, bolt-up, gasket selection, and alignment.

Accessibility Lapses: Designs need to consider future inspection and repair. Tight-packed piping or inaccessible routing create long-term maintenance headaches.

Ignoring Documentation or Compliance: Every design must meet codes and standards, with clear documentation. Unapproved changes or missed records can threaten safety and operations.

What Comes Next: Building Advanced Expertise

With experience, engineers will gain more familiarity with code requirements (ASME, API, etc.) and find opportunities to branch out into design, maintenance, integrity, management, or project execution. Building expertise in the following areas will be beneficial for long-term career growth while also improving safety and reliability.

- Stress analysis: Predicting and managing combined loads and expansion

- Material science: Selecting advanced alloys and corrosion protection

- Non-destructive inspection: Using radiography, ultrasound, and other techniques for integrity assessment

- Layout optimization: Balancing flow efficiency, safety, and accessibility

- Root-cause analysis: Investigating failures and improving reliability

Skills and Practices to Develop Early

- Communicate across disciplines: Work with process, civil, instrumentation, and maintenance teams

- Thoroughly review drawings/specifications: Confirm every detail, pipe class, routing, and support

- Walk the site: Observing real piping systems fosters practical intuition

- Leverage lessons learned: Analyze past incidents, maintenance records, and reliability data

- Consider operational impacts: Every design choice affects safety, reliability, and cost downstream

- Attend an Equity Technical Institute training course on process piping or piping vibration.

Building Confidence in Piping Systems

Piping systems are essential for safe and efficient facility operation. By understanding core principles and common failure modes, such as the vibration issues highlighted in our case study, early-career engineers can better identify risks and contribute to robust designs.

Every system you design, inspect, or maintain supports operational integrity. By connecting theoretical design to practical site realities and seeking mentorship from experienced colleagues, you will build the experience-backed knowledge necessary for success. Mastering these fundamentals is a vital step toward advanced engineering roles and long-term industry impact.

If you have a question for the author or would like follow-up, please fill in the form below: