Two-phase flow is one of the most common—and most challenging—sources of piping vibration in process facilities. When both liquid and gas phases are present, the significant density difference between them creates large velocity differentials, which can generate large dynamic forces that are transferred to the piping. These forces can excite the natural frequencies of piping and lead to fatigue failures if not properly addressed. Complicating matters, piping systems that experience two-phase flow often operate at elevated temperatures, making them difficult to restrain without inducing excessive thermal expansion stresses. Understanding the fundamentals of two-phase flow, recognizing how different flow regimes affect vibration response, and applying appropriate analysis methods are essential skills for diagnosing and solving these problems.

Two-Phase Flow Fundamentals

For single-phase turbulent flow in a pipe, dynamic forces are transferred to the pipe wall with turbulent energy concentrated at low frequencies and attenuating at higher frequencies. If the piping is not adequately supported (i.e., has a low natural frequency), these dynamic forces can excite the piping’s natural frequencies, leading to random vibration. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as flow-induced turbulence (FIT) or flow-induced vibration (FIV) [1].

For two-phase flow, the turbulent forces transferred to the piping can be significantly more severe than single-phase flow. In many process facilities, two-phase flow occurs in piping connected to heat exchangers or fired heaters due to partial vaporization of the fluid when heated. To compound this issue, the high temperatures involved cause significant thermal expansion in the piping, making it difficult to restrain without inducing excessive stress. Piping engineers frequently use spring hangers to support the piping weight, but these provide almost zero stiffness to resist vibration forces. For these reasons, piping with two-phase flow in process facilities is particularly susceptible to high vibration.

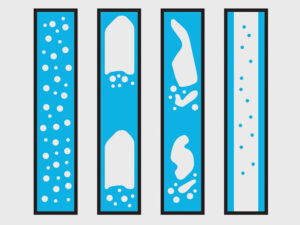

Two-phase flow is categorized into different flow regimes, and the flow regime directly influences how the piping vibrates. Figure 1 shows examples of flow regimes for both vertical and horizontal flow orientations.

The flow regime depends on many factors: liquid and gas flow rates, densities, viscosity, surface tension, orientation (horizontal, vertical, or slanted), and direction (upward or downward). It can also depend on the straight length of piping and upstream conditions. Flow bends, such as flow through a piping elbow, can cause the flow regime to change due to a combination of centrifugal forces, inertia forces, gravity forces, and buoyancy forces [2]. In practice, predicting the flow regime of two-phase flows can be very difficult.

Extensive experimental testing and empirical formulas exist for predicting flow regimes; however, they are not applicable for all scenarios. Two-phase flow is well studied for reservoirs and pipelines, where systems involve very long, straight sections without elbows or other directional changes. In process facilities, most of the flexible piping susceptible to vibration from two-phase flow is constructed with many changes in direction for connection to process vessels and other components. Therefore, care should be taken when applying published flow regime correlations to piping in process facilities.

Flow regimes are commonly characterized using flow regime maps based on empirical testing with long, straight sections of piping (Figure 2). Many of these maps are based on experimental testing of air-water mixtures with small pipe diameters and do not represent the exact physics occurring in process facilities. Alternatively, mechanistic models can predict the flow pattern for any orientation of piping based on the gas and liquid properties and flow rates [5]. These mechanistic models are generally more accurate than flow regime maps; however, they typically do not account for the effects of fluid inertia due to changes in flow direction. Considering these inertia effects requires computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations [2][6], which are computationally expensive and not practical for all applications.

Horizontal Flow Regimes

For horizontal flow, buoyancy effects cause the liquid and gas to separate to the bottom and top of the pipe, respectively.

At low velocities, the liquid flows on the bottom and the gas on the top of the pipe, known as stratified flow. As velocity increases, waves start to form at the liquid-gas interface (wavy flow). If velocity increases further, these waves can become unstable and span the entire cross section of the pipe, leading to intermittent slug flow. Formation of slug flow typically requires sufficient straight length of pipe since the mixing of liquid and gas fractions at directional changes (e.g., pipe elbows) can prevent the liquid wave from covering the entire cross section and inhibit slug formation.

At higher velocities, the flow transitions to either bubble, annular, or mist flow depending on the gas and liquid mass fractions.

Vertical (Upward) Flow Regimes

For vertical upward flow, buoyancy effects cause gas to rise through the liquid.

With low gas fractions relative to the liquid flow rate, bubble flow occurs. As the gas flow rate increases, small bubbles combine into larger Taylor bubbles that occupy almost the entire pipe cross section, referred to as plug or slug flow. These Taylor bubbles rise through the liquid due to buoyancy effects. As gas velocity further increases, Taylor bubbles become unstable and break apart once formed, known as churn flow. At even higher gas velocities, annular flow occurs, where the liquid forms a film on the pipe wall with gas flowing through the center.

Random Vibration Fundamentals

Periodic vibration is repeatable and consistent, or in other words, the time waveform repeats itself. Common causes include mechanical resonance from rotating equipment, acoustic pulsation from reciprocating machinery, and mechanical resonance from flow vortex shedding (often a problem for flow across thermowells). Piping vibration is commonly characterized by calculating a crest factor (CF), which is the ratio of the peak vibration velocity (vpk) to the root-mean-squared (RMS) vibration velocity (vRMS).

For a perfect sinusoidal vibration at one frequency, the crest factor is 1.414 (√2). Multiple frequency components increase the crest factor. For periodic vibration, since the time waveform is repeatable, data only needs to be collected for a short period to accurately measure peak vibration and the crest factor. Figure 3 shows an example of periodic vibration data collected on piping connected to a reciprocating compressor.

On the other hand, random vibration is not repeatable. Common causes include turbulent flow in piping, two-phase flow in piping, and non-resonant vortex shedding forces on vessels and stacks. While random vibration can be characterized by a crest factor, the crest factor will not be consistent because the time waveform is not repeatable. In general, vRMS for random signals remains relatively constant, but vpk varies over time [7]. Figure 4 shows random vibration collected on the crossover piping of a fired heater.

Since the crest factor cannot always be reliably measured with random vibration, random vibration is commonly characterized by an assumed statistical distribution. Most random piping vibrations closely match a Gaussian distribution. To define a Gaussian distribution for vibration, only the vRMS needs to be known. The caveat is that random piping vibration is not always well-represented by a Gaussian distribution. Impacts of the pipe against another surface and intermittent flow are common reasons why random piping vibration may deviate from Gaussian behavior.

One way to determine if random piping vibration represents a Gaussian distribution is to calculate the kurtosis of the signal. Kurtosis measures how often outliers occur and how large they are. An ideal Gaussian distribution has a kurtosis of 3.0. If the kurtosis of random piping vibration is approximately 3.0, then a Gaussian distribution will closely represent the vibration data. If the kurtosis is significantly higher than 3.0, alternative methods are required. Figure 5 shows examples of real-world random piping vibration data with and without high kurtosis.

The upper plot in Figure 5 is from vibration caused by high flow turbulence, resulting in a kurtosis of approximately 3. The amplitude changes with time, but there are generally no sharp transitions. The lower plot is from vibration caused by slug flow and the impact of piping against a support. Impact events cause large spikes in vibration, resulting in a kurtosis over 11. It should be noted that for random vibration, it may be difficult to identify high kurtosis just by looking at the spectrum. Calculating kurtosis and reviewing the time waveform are important steps when assessing random piping vibration.

Connecting Two-Phase Flow to Vibration Response

For two-phase flow vibration, there are two primary mechanics: intermittent and turbulent.

Intermittent vibration is caused by slug or plug flow and produces large impacts at pipe bends as slugs traverse the piping. Each impact causes the piping to vibrate. Turbulent vibration is caused by the chaotic and random nature of two-phase flow. Churn flow in particular generates large turbulent forces due to Taylor bubbles breaking apart. The vibration is random in nature, increasing and decreasing over time, but without one large event causing the response. For some problems, both intermittent and turbulent two-phase flow are present and contributing to vibration.

From an analysis perspective, vibration dominated by turbulence will likely exhibit a nearly Gaussian response (kurtosis ≈ 3), while vibration dominated by intermittent flow can exhibit a non-Gaussian response (kurtosis > 3), though there are cases where slug flow can also cause a Gaussian response. As shown above, non-Gaussian vibrations result in larger effective crest factors, causing more damage for the same RMS velocity. For this reason, it is common practice to design piping to avoid intermittent flow regimes.

The distinction between turbulent and intermittent flow is critical when deciding how to remediate piping vibration. Vibration from turbulence can be remediated by reducing turbulence (reducing flow velocity or eliminating flow turns/obstructions) or adding piping supports to increase stiffness. Vibration from intermittent flow can be mitigated by changing the flow regime or adding supports.

For situations where two-phase flow vibration is thought to be caused by slug flow, one potential solution is decreasing the pipe diameter (increasing fluid velocity) to change the flow regime and avoid slug formation. However, decreasing pipe diameter also increases turbulence, which could create new vibration issues. If this approach is considered, the effect of increased velocity should be evaluated for potential turbulence-induced vibration. Most importantly, it is essential to verify that vibration is actually caused by slug flow in the first place. If it is not, decreasing the diameter will likely make the vibration significantly worse.

Case Study: Heater Inlet Piping Vibration

At a process facility, inlet piping on one of the heaters had a history of vibration issues. The piping was NPS 8 and designed to 625 psig at 800°F (426.67°C). As part of an independent study, a section of pipe was reduced to NPS 6 since slug flow was thought to be occurring in the NPS 8 piping.

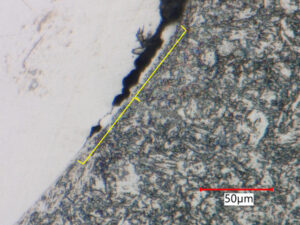

After the diameter change, two piping vibration-related failures occurred at the same location on a dummy leg support. The dummy leg was replaced with two all-thread hangers, which removed the high stress concentration failure location but made the piping significantly less stiff and visibly increased vibration. Vibration measurements were recorded and a stress analysis was performed to determine the severity.

Vibration measurements were recorded at six locations on the piping. There were two dominant vibration frequencies. The 3.2 Hz vibration occurred in the N-S direction while the 5.5 Hz vibration occurred in the E-W direction.

A dynamic model of the piping was created to determine vibration stresses based on measured data. Support stiffnesses were tuned to match the operating deflection shape (ODS) to the modeled harmonic displacements at the two dominant frequencies. Shown in Figures 6 and 7 are animations of the measured ODS of the piping at the two dominate frequencies.

Location 3 had a vibration velocity of 1.25 ips RMS in the N-S direction and 0.70 ips RMS in the E-W direction. Since stresses were calculated at every location in the piping model for each frequency, the stresses were combined by taking the RMS of the two calculated stresses. The stress at each location was then compared to the allowable RMS stress. Eight locations were predicted to have stresses exceeding the endurance limit, confirming that additional supports were needed to reduce vibration.

Thermal expansion stresses in the piping were considered when designing new supports. The existing piping already had high thermal stresses, limiting options for support locations, and only a few locations had existing structural steel in close proximity. After several design iterations, two new supports were identified (Figure 8). This design increased piping stiffness while keeping thermal expansion stresses within allowable limits. Each support consisted of rigid sway struts connected to existing structural steel. After the new supports were installed, vibration was remeasured and found to have significantly decreased to within acceptable levels.

Conclusions

Two-phase flow piping vibration presents unique challenges due to the complex interaction between flow regimes, dynamic forces, and piping system characteristics.

The distinction between turbulent and intermittent vibration is critical for selecting appropriate remediation strategies. Decreasing piping diameter to avoid slug flow can inadvertently create vibration issues from excessive turbulence, and this approach should only be pursued after confirming that slug flow is the root cause.

For random vibration analysis, kurtosis provides essential information about the vibration. High kurtosis (significantly greater than 3.0) indicates non-Gaussian behavior requiring adjusted crest factors for accurate fatigue assessment.

Designing additional supports for high-temperature piping requires a careful balance between increasing vibration resistance and maintaining acceptable thermal expansion stresses. Sway struts can be an effective solution, but proper installation is critical.

If vibration issues from two-phase flow are occurring at your facility, consider having a detailed engineering assessment performed to properly diagnose the root cause and develop an effective remediation strategy.

If you have a question for the author or would like follow-up, please fill in the form below:

References

[1] Energy Institute, Guidelines for the avoidance of vibration induced fatigue failure in process pipework, 2nd edition, 2008.

[2] H. Zhu, Y. Hu, T. Tang, C. Ji, and T. Zhou, "Evolution of Gas-Liquid Two-Phase Flow in an M-Shaped Jumper and the Resultant Flow-Induced Vibration Response," Processes, vol. 10, no. 10, p. 2133, 2022.

[3] O. Bamidele, W. Ahmed, and M. Hassan, "Characterizing two-phase flow-induced vibration in piping structures with U-bends," International Journal of Multiphase Flow, vol. 151, p. 104042, 2022.

[4] G. Hewitt and D. Roberts, "Studies of two-phase flow patterns by simultaneous x-ray and flash photography," Atomic Energy Research Establishment, Chemical Engineering Division, Harwell, England, 1969.

[5] H. Zhang, Q. Wang, C. Sarica, and J. Brill, "Unified Model for Gas-Liquid Pipe Flow via Slug Dynamics—Part 1: Model Development," ASME Journal of Energy Resources Technology, vol. 125, no. 4, pp. 266–273, 2003.

[6] T. Firmansyah, M. Rakib, M. Karakaya, M. Musharfy, and M. Suleiman, "Mitigating flow induced vibration in heater radiant coil," Oil & Gas Science and Technology - Rev. IFP Energies nouvelles, vol. 73, p. 28, 2018.

[7] L. Breaux, S. McNeill, and G. Szasz, "Fitness-for-service assessment of piping subject to random vibration, PVP2016-63695," in Proceedings of the Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, 2016.